The second largest temple in Poland.

History of Szczecin

THE BURGWALL OF THE GRIFFIN

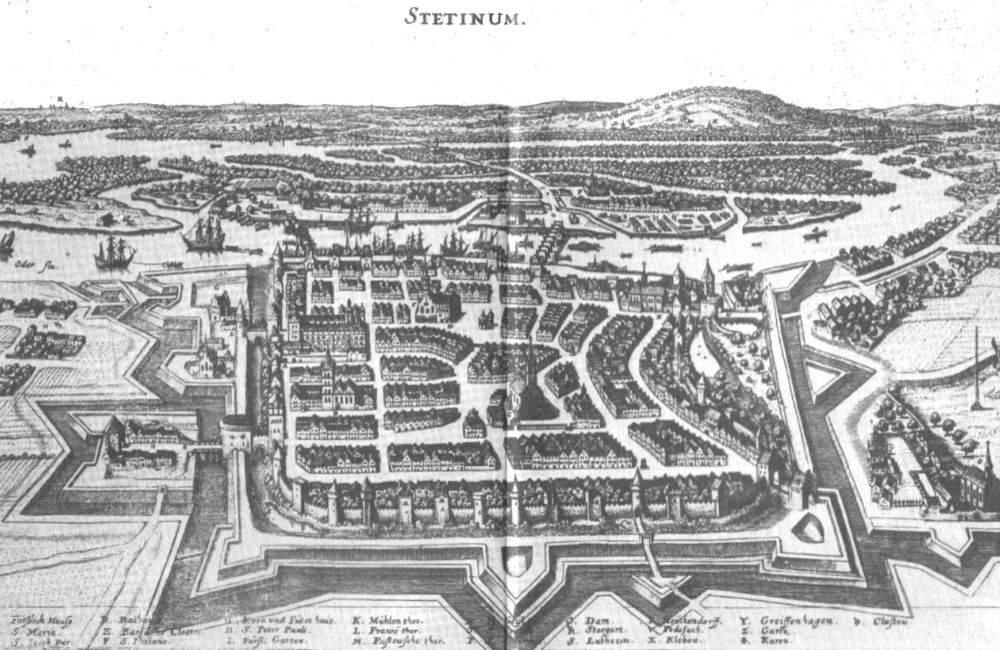

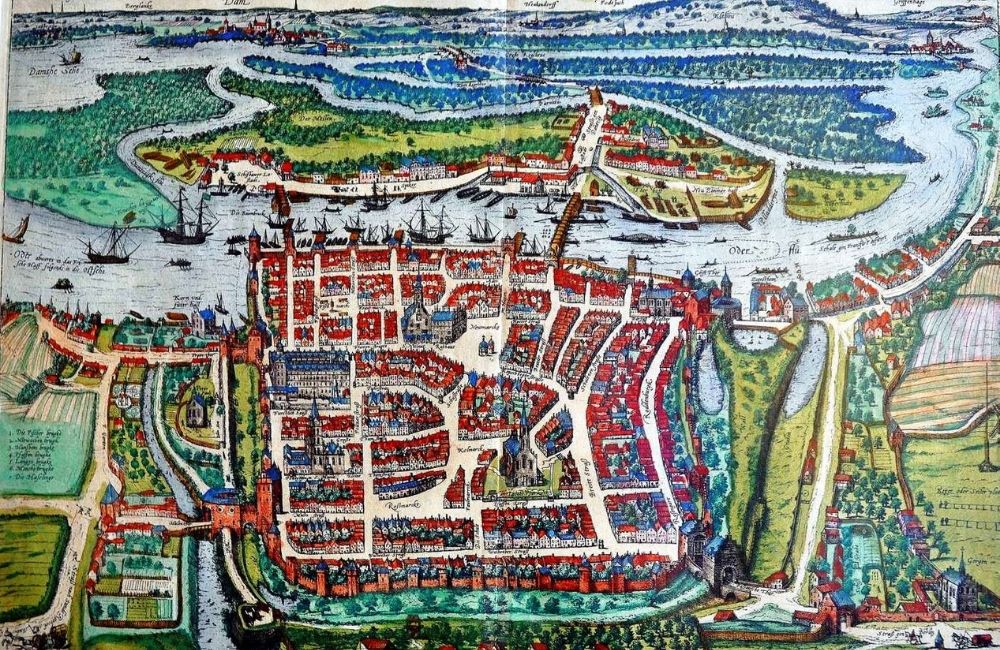

Szczecin – the former capital of the Duchy of Pomerania under the reign of the dukes of the Griffin dynasty, and now the capital of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, is the largest city in Western Pomerania. Historically, the city was also known as Sasin, Sedinum, Stetinum and Stettin.

Its current coat of arms depicts a crowned griffin's head. The griffin, a hybrid of a lion and an eagle, is a mythical creature with rich symbolism. Griffins pulled the chariots of the gods and watched over treasure, and knights put their images on shields to scare off opponents. In their nests, griffins laid sapphires instead of eggs, and their feathers were believed to cure blindness. In today's Szczecin, they look at us from the facades of many buildings, tenements and street water pumps. An imposing winged griffin is located on the square in front of the Town Hall, shining in radiant colours in the evening.

THE HOUSE OF GRIFFINS AND THE DUCHY OF POMERANIA

The oldest settlement village on what is now known as Castle Hill was established as early as in the 8th century.

In 1124, following the example of Duke Wartislaw I (the first known representative of the House of Griffins) and a group of nobles, the citizens of Szczecin were baptised. At the request of Bolesław III Wrymouth, Bishop Otto of Bamberg undertook two Christianising missions. The wooden manor house of Duke Wartislaw was located in the neighbourhood of a Triglav Pagan temple.

On 3 April 1243, Duke Barnim I the Good granted Szczecin a town charter fashioned after the Magdeburg Charter. In 1346, his grandson Barnim III the Great, against the will of Szczecin's patricians, initiated construction of the Stone House, the forerunner of the present-day castle. The medieval city area (ca. 54 ha, or 133 acres) remained unchanged for several centuries.

The Griffins' rule over Szczecin lasted for half a century. During that period, the city became the seat of the dukes and a member of the Hanseatic League. Its relations with the Hanse (13th–14th c.) were primarily based on grain and fish trade. Szczecin was suspected of giving advantage to pirates at that time due to its half-hearted efforts in fighting them. Craftsmen and their families comprised half of the city's population. Notable examples of Gothic architecture were constructed at that time; now they are part of the European Route of Brick Gothic (the Old Town Hall and three churches).

At the end of the 15th century, Prince Bogislaw X unified the Duchy of Pomerania and made Szczecin its capital. His second wife was Anna Jagiellon, daughter of the Polish King Casimir Jagiellon. At the beginning of the 17th century the Duchy was ruled by Philip II and Francis I of Pomerania – both well-educated enthusiasts of art and science, and sponsors of the arts. They built the fifth (two-storey) museum wing to create the second castle courtyard. By the initiative of Duke Philip II, Eilhard Lubinus made the Great Map of the Duchy of Pomerania, decorated with city engravings and a genealogical tree of the House of Griffins. This masterpiece of cartography is now displayed in the Castle of the Pomeranian Dukes.

In 1534, Lutheranism was introduced across the whole Duchy of Pomerania. The chief Pomeranian reformer was Johannes Bugenhagen, a friend of Martin Luther. Using property of the Catholic Church taken over by the dukes of Pomerania, the Ducal School (1543) was established, an institution with a status between that of a Latin school and a university.

THE SWEDISH PERIOD

The Swedes took over Szczecin during the Thirty Years' War. In 1630, the Swedish army of Gustav II Adolf arrived at the walls of the city. In 1637, Bogislaw XIV, the last duke of the House of Griffins, died without an heir. The Treaty of Westphalia, which marked the end of the Thirty Years' War, was signed in 1648 in the Town Hall of Osnabrück, and sealed the split of Pomerania. The western part, including Wolin and Szczecin, went to Sweden for almost a century. The Sweden-Brandenburg rivalry continued. As an expression of gratitude for help and the heroic defence during the siege by Elector of Brandenburg, King Charles XI of Sweden awarded the town a new coat of arms by adding the Swedish lions to the crowned griffin's head, along with the Vasa royal crown and a laurel wreath. The town was also surrounded by a ring of star-shaped bastion fortifications.

PRUSSIAN FORTRESS AND FRENCH OCCUPATION: 1806–1813

2 million thalers: that was the price of acquiring Szczecin "for eternity". In 1720, Frederick William I of Prussia paid the compensation to Queen Ulrika Eleonora of Sweden. The commander of the military garrison was Christian August von Anhalt-Zerbst, father of future empress Catherine II the Great, who was born in Szczecin (1729). New fortifications from 1724–1740 transformed Szczecin into a formidable Prussian fortress with three forts. It took 43 million bricks and 9 million thalers to build them. However, the military function of the Szczecin fortress hindered its urban development for a long time. Two Baroque city gates survive to this day: the Port Gate (formerly the Berlin Gate) and the Royal Gate (formerly the Anklam Gate). Huguenots who emigrated from France for religious reasons settled in the city. They were granted special privileges, had their own capital, and established factories, thus reviving trade, services and industry. The bourgeois elite ran art salons, while the formation of scientific and cultural societies contributed to historical research on Pomerania's past and the creation of the city museum.

Modern and formidable, the fortress of Szczecin fell when confronted by Antoine Lasalle, a shrewd French general. General Friedrich Gisbert Wilhelm von Romberg, the Prussian commandant of the fortress, was misled by the mock manoeuvres of 600 cavalry and frightened by the threat of a siege and looting of the city. When giving up the fortress, he gave his favourite porcelain pipe to the French strategist as a token of recognition. The residents of Szczecin attended the balls and fencing lessons organised by the Napoleonic army. However, their lives were not easy. The city was forced to pay a high contribution and maintain around 8,000 soldiers (who were quartered in the barracks, the houses of the townspeople, and in a temporary camp).

In the first half of the 19th century, the military authorities became more open to the idea of removing Szczecin's fortress status. As a result, the city was connected by rail to Berlin and the New City (an attractive military-residential complex) was established. Industrialisation and urban infrastructure investments (gasworks, water supply systems) progressed, and modern facilities were established (the "Vulcan" shipyard, power station, automobile factory of the Stoewer brothers, cement factory, sugar refinery, ironworks, paper mill, along with the synthetic fibre and chamotte brick factory).

From 1873, Szczecin implemented the orders of the Ministry of War abolishing fortress restrictions. The areas vacated by the army became a challenge for urban planners and architects. That moment marked the beginning of the dynamic expansion of the city. The commission for creating a comprehensive development plan for city areas was led by Konrad Krühl. The plan was partly based on James Hobrecht's concept. Szczecin gained its distinctive squares with a radial pattern of streets. Redevelopment of the city centre was initiated, and eclectic tenement houses were modelled on those of Berlin. Architects paid great attention to their appearance and made sure that the front facades were impressive, featured rich ornaments and were decorated with sculptures (although these were usually selected from stencils and construction catalogues). As a result, the houses became prestigious "tenement palaces". In the second half of the 19th century, the city became a major industrial port. From 1879, an increasing area of the city had access to horsecars, and an electric tram service was introduced in 1896.

METROPOLITAN SZCZECIN

The turn of the 19th and the 20th century brought Szczecin its modern urban character. One important step in that process was the inclusion of urbanised (but formerly independent) suburban settlements and towns into Szczecin. The city quickly made up for the lost years and took full advantage of its prestigious position as the capital of the region. Between 1902–1921, the Haken Terrace (now the Chrobry Embankment) was constructed. It is a representative boulevard with monumental buildings, pavilions and a large basin with a fountain at its base.

PERIOD OF WARS

WWI – While military operations did not affect the city directly, the conflict brought inflation, the collapse of many businesses, unemployment and homelessness. During the interwar period, Szczecin lost its economic importance. Revolutionary actions and strikes took place. Szczecin underwent an economic collapse and was hit by hyperinflation. In Szczecin, unlike the rest of Western Pomerania, Paul von Hindenburg received more votes than Adolf Hitler in the presidential election. The gradual revival of business was artificially accelerated after Hitler's rise to power, following the promised elimination of unemployment and efforts to build a military-oriented economy. On the Kristallnacht of 1938, the Nazis burned down the synagogue located near the present-day Pomeranian Library on Dworcowa Street.

15 October 1939 – the administrative boundary of the city was extended to create Greater Szczecin (by including the towns Police and Dąbie, as well as other areas). The city's area increased almost six-fold.

WWII – the city's economy served the military needs of the Reich. Szczecin was given the highest air bombing threat level. The industrial areas on the Oder and in the Old Town suffered most from the bombings.

AFTER 1945

From 26 April 1945, the Soviet army occupied Szczecin. Following the Potsdam Conference, the city was given to Poland as compensation for the loss of its former eastern lands to the Soviet Union. The official takeover of the city by the Polish administration took place on 5 July 1945. "This is the moment we have dreamt of and desired for years", reads the diary of Piotr Zaremba, the first mayor of post-war Szczecin. Official propaganda needed an historical reason to justify the rapid settlement of these lands. In order to convince people, the authorities used emotional arguments about "the ancient Slavic lands and the return to the Piast tradition". The population was almost completely replaced. 8 million tonnes of debris were removed by 1958. Undamaged bricks were sent to Warsaw in response to the propaganda slogan "The whole nation builds its capital".

In its post-war history, Szczecin was a leader of the labour movements which accelerated the radical political changes of 1989. The protests of December 1970, the strikes of August 1980, and other key events are commemorated by the Dialogue Centre Upheavals, the youngest branch of the National Museum in Szczecin. In 2016, this underground museum (designed by Robert Konieczny of the KWK Promes studio) was recognised in an international competition as the Best Public Space in Europe. Another building nearby, the Philharmonic Hall, has also garnered worldwide acclaim.

St. James Arch Cathedral

Szczecin's Underground Routes

The largest civil shelter in Poland.

The December ’70 Trail

The history of Szczecin abounds with turbulent events.

Rector’s Office of the Pomeranian Medical University

Neo-Renaissance building and its 68-metre tower were erected between 1900 and 1902

A fragment of medieval city walls

preserved fragment of medieval fortifications

Old City Hall

A Gothic building from the 15th century.

Harbour Gate

The most impressive baroque fortress gate in West Pomerania.

Royal Gate

This baroque fortification was intended to defend access to the city from the north.

Gothic Church of St. John the Evangelist

The one of the oldest building in Szczecin.